When we decided to buy this place, we didn’t commission a survey of the buildings, but we did fork out for a survey of the trees. With the house, there was so much wrong a survey would have been largely pointless; the roof is threadbare and collapsing, the interior is a horror show (more of that in coming weeks) and the exterior walls are either so old and thick they are never coming down, or so crumbling and patched its clear where they need work. The trees, however, were a different story. Even though I grew up on the edge of a beautiful deciduous forest and spent most of my childhood surrounded by magnificent trees, I realised I didn’t have much of an idea about how to look after them; and with 2.5 acres crammed with the buggers I was going to have to address that ignorance pretty fast.

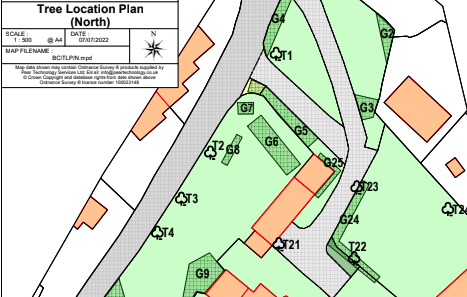

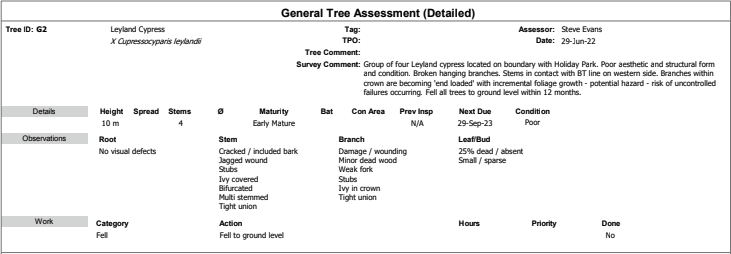

Fortunately for us, we found Steve, a knowledgeable, environmentally aware arborist living in the next village, and a few months after we had our offer accepted, his very thorough report landed in my inbox. I’ll share a few pages of it below to give a sense of how a tree report works. There are too many trees to list individually, and as the majority of our trees are sycamore – which grow like weeds in this part of the world – it made much more sense to classify the trees in similar groups (labelled G) and then to call out any trees of significance individually (labelled T). Each group or individual tree is then assessed and an action plan proposed. Our report is 40 pages long, so there is a lot to do!

The most significant trees we have here are four ancient yews, which sit in two pairs at either end of the walled garden. Steve reckons these were planted when the house was built, which English Heritage estimates to be mid 17th century. These beauties are coming up on the their four-hundredth birthday, and at ground level they look like a mess, with a tonne of dead wood crowding out their bases. However, from above, you can see how healthy and vigorous they still are. The two yews at the bottom of the garden are filled with thick, creeper-like vines from an out-of-control elaeaganus bush, which was probably meant to be a small shrub forty or so years ago, but which was never pruned, and has become staggeringly huge in the interim. It is crowding out the lower yew branches and weighing them down. Fortunately, with some expert care, these trees should be able to flourish again and grow new stems from the old growth. We now have a care plan in place for them, starting with cutting back the ivy growing up their trunks (more on ivy later).

We also have a few groups of problematic trees; in particular a bunch of Leyland cypress trees. These were presumably planted as hedging some decades ago, but – as we have started to realise – the thing about trees and shrubs is that they don’t tend to stop at a few metres. Leave them alone in the right conditions (and Cornwall’s warm, damp climate is paradise for many trees) and they will just keep growing. Our leylandii are massive now, which would be fine if they weren’t also at the end of their lives and about to start shedding branches on the surrounding roads. They will need to come down, and this involves tricky things like getting British Telecom to take down inconveniently placed phone lines, and potentially shutting the road for a while so a tree surgeon can safely fell them. This all costs money, of course. We’ve had quotes from local tree surgeons and settled on someone to do the work. Costs vary tremendously, but a big complex tree can easily cost a thousand pounds or more to fell. For us, one of the fortunate side effects of this work is that we can use the resulting wood for firewood, carpentry and mulch for paths and beds. No part of any tree is going to be wasted: it will all be reused on site in one form or another, feeding the next generation of trees.

Then there are the sycamore: hundreds of them at all stages from seedling to fully mature. Some are very beautiful and majestic; others are scabby and damaged. The major culprit damaging them turns out to be hungry squirrels, for whom sycamore sap is apparently a delicious treat. The trouble is, the squirrels don’t know how to stop when it comes to their sap excavations, and tend to remove rings of bark from stems, which effectively kills off that part of the tree. All over our site we see big branches which have come down this way, and patches of leaves turned prematurely yellow as the branch dies off. Many of these branches will need to come down for safety reasons. Fortunately for the squirrels, there are more than enough trees to keep them fed in the coming years.

However, the main challenge we face is not to do with the trees themselves, but with the ivy which covers almost every inch of our woodland garden. It snakes up the trees everywhere, which not only blocks out a lot of light in an already dark place, but increases the wind load of the trees, making it more likely that branches and even whole trees will come crashing down. With report in hand, I am making my way steadily around the whole site, cutting back the ivy in metre-tall strips around each trunk. This method is apparently more effective than just cutting the ivy stems at the base of the tree, as it makes it more likely you won’t miss any, but also enables you to see and deal with any new growth as it appears. I’ve added some before and after pictures below to show what it looks like.

Another tactic is crown raising: many of our sycamores have been coppiced (cut to the ground to encourage new stem growth) in the past, which leads to a lot of low-growing stems which block out light. On Steve’s advice we bought a rather amazing German lopping tool, which extends to a height of four metres and enables us to cut off much of the lower growth while leaving the crown intact. This will help us a lot to bring more light and sun to dry out the damp walls of the house, and to let in more light for growing vegetables in the kitchen garden (when I get around to planting it).

Much of what we want to do with this place is dependent on us getting the tree work done first: making the site and surrounding lanes safe, planting the garden, protecting the walls of the house and garden, making paths, giving space to the builders to work. For anyone taking on a site with significant numbers of trees, a tree survey is a great way to understand and prepare your site for the work you intend to do and to know how to protect and preserve your precious trees.